Any maths student will be familiar with the fact that there are pairs of integers whose squares add up to the square of another integer, for example 3^2 + 4^2 = 5^2.

Any maths student will be familiar with the fact that there are pairs of integers whose squares add up to the square of another integer, for example 3^2 + 4^2 = 5^2.

Examples of these so-called Pythagorean Triples have been known for millenia.

Fermat’s LastTheorem posited that there are no integers for which a^n + b^n = c^n where n is an integer greater than or equal to three.

There is a fascinating documentary by Simon Singh about the proof by the English mathematician Andrew Wiles and his very lengthy proof in 1995.

It may be found here.

Pierre de Fermat was a famous mathematician who lived in the 17th Century in southern France. He is best known for Fermat’s principle that explains how light travels and Fermat’s Last Theorem in number theory, which he described in a note at the margin of a copy of his book Diophantus‘ Arithmetica.

Fermat’s Last Theorem is possibly the most well-known theorem in mathematics. It was suggested by Fermat, and indeed he said that he had a proof for it but this was never published. A theorem without a proof is a strange thing indeed – not a theorem but a conjecture – a mathematical law which has not been proven.

It took over three hundred years and seven years of work for a British mathematician, Andrew Wiles, based at Princeton University in the USA to solve the problem.

The idea of Fermat’s Last Theorem can easily be understood with a few examples and a calculator. Challenge students to find a case where n is greater than two. They may well not believe that such cases don’t exist.

The documentary lasts 50 minutes and first explains what Pythagoras Theorem is. It then extends the idea to any power to a whole number and explains the hint by Fermat that he had found a proof that there are no integer solutions to the equation

x^2 + y^2 = z^2 for n>2.

It then discusses quite clearly how a problem in one field of mathematics can be translated into a different problem in another area of mathematics. So it was that the original problem was translated into a different problem to which a solution needed to be found. Andrew Wiles, through a flash of inspiration, which he describes vividly, came to this solution.

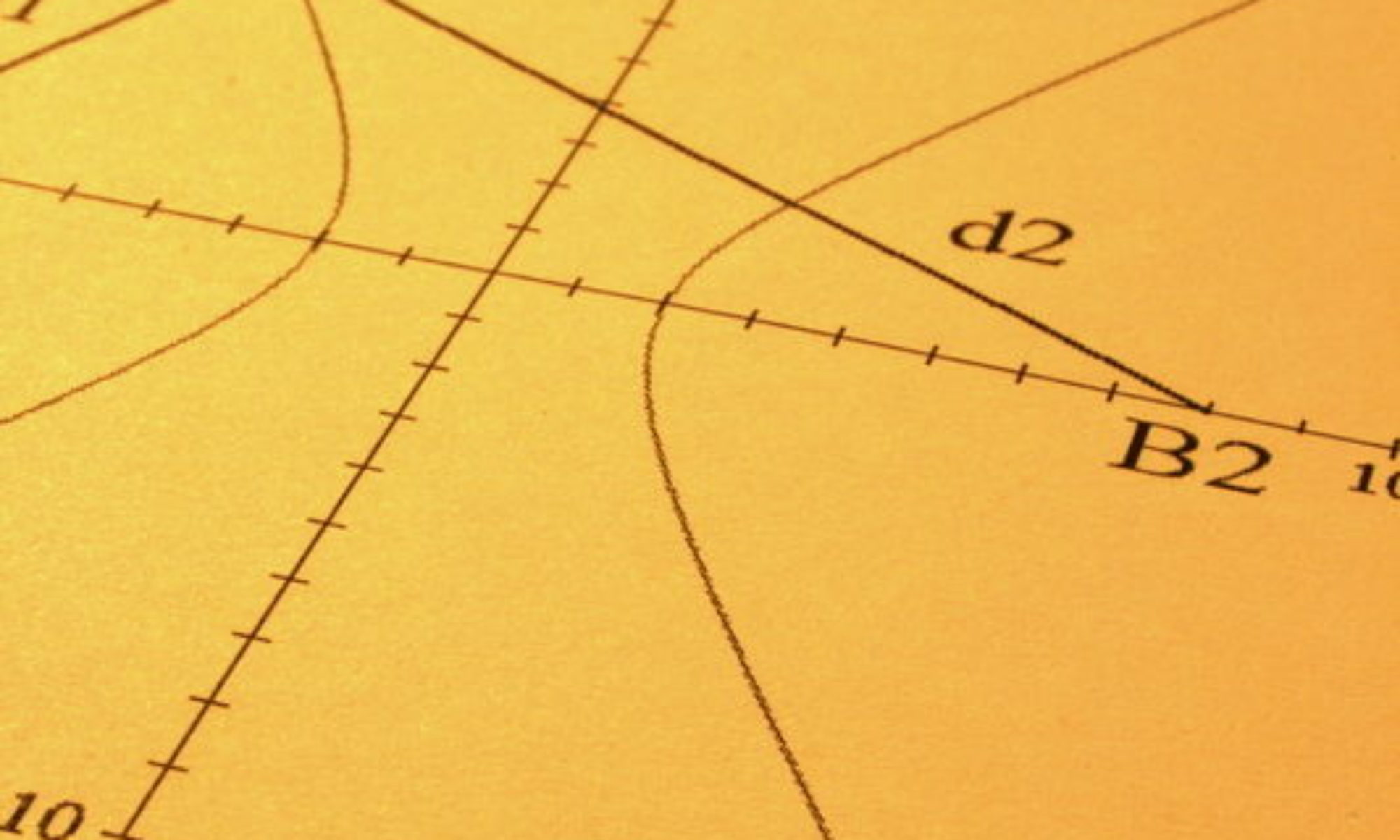

So, you’ve just been handed a brand new graphical display calculator (GDC) for your IB maths course. There’s a good chance that you have been given a Texas Instruments Ti-84+ or a Casio FX-9860. If you did the Middle Years Programme, then you may have used a GDC before. But if you took the GCSE or IGCSE, then it will be new to you.

So, you’ve just been handed a brand new graphical display calculator (GDC) for your IB maths course. There’s a good chance that you have been given a Texas Instruments Ti-84+ or a Casio FX-9860. If you did the Middle Years Programme, then you may have used a GDC before. But if you took the GCSE or IGCSE, then it will be new to you.